Black History Case Files is more than a project—it’s a mission. We are dedicated to uncovering, documenting, and revealing the undeniable truths of history that have too often been ignored, rewritten, or deliberately buried. If history has been silenced, we give it a voice. If the record has been distorted, we set it straight. And if the truth is hidden beneath layers of time, bias, or neglect, we will dig it up and bring it back into the light. Every page, every case, and every discovery is part of a larger journey: to restore dignity, reclaim identity, and reconnect generations with the heritage that belongs to them. History is not lost—it is waiting to be found. And we are here to find it.

Echoes in Stone: Nubians at Persepolis and Judah at Lachish

Echoes in Stone: Nubians at Persepolis and Judah at Lachish

Echoes in Stone: Nubians at Persepolis and Judah at Lachish

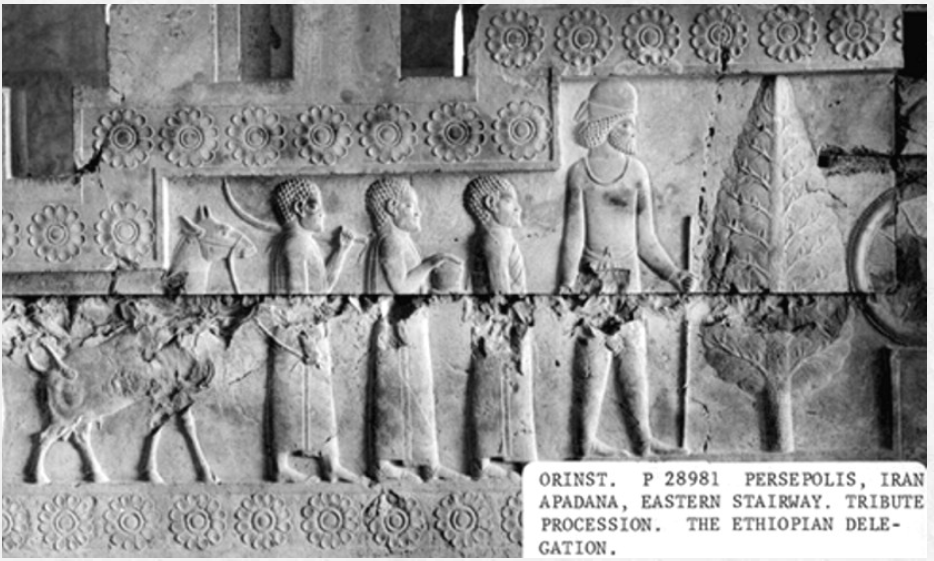

When we examine the grand Apadana reliefs at Persepolis—specifically the East Stairs, where subject peoples of the empire bring tribute to the Persian king—one group stands out: the Nubians. Their features, carved with extraordinary precision, reveal a familiar detail. Their hair is represented not as flowing locks or stylized waves, but as short, coarse, tightly curled bumps. The sculptor painstakingly chiseled around 80 small raised knobs across each scalp, a method long associated with the portrayal of African peoples.

What makes this discovery even more compelling is the comparison to the Lachish Relief. In that Assyrian monument of conquest, the men of Judah are also shown with short woolly hair, carved in the same raised-bump technique. In Lachish, the prisoners appear under guard, executed, impaled, or marched into exile—yet every one of them is marked by the same tightly coiled hair. Some even wear short curly beards, but the consistency of the scalp hair is undeniable: dense, short, and woolly, captured in dozens of raised stone curls.

The Persepolis Nubians provide a vital cross-reference. While they appear beardless, their hair texture and style is identical to that of the Judeans at Lachish. The implication is striking: across two empires, separated by geography and culture, artists used the same iconographic language to capture the same physical reality—a people with short, tightly coiled, African-type hair.

This is not artistic coincidence. It is a visual code of identity, repeated in both Mesopotamian and Persian imperial art. At Persepolis, the Nubians bring tribute; at Lachish, the Judeans are led in defeat. But the carved hair unites them in a shared visual tradition, confirming the ethnicity of Judah as recorded by the eyes and hands of ancient conquerors.

The evidence speaks in stone. In Lachish and in Persepolis, in Assyrian palaces and Persian stairways, the same story emerges: the men of Judah bore the short, woolly hair and African features that their conquerors could not ignore—and carved forever into history.

Side-by-Side: Persepolis vs. Lachish

Persepolis (Apadana East Stairs – Nubian Delegation)

-

The Nubians appear bare-headed, without beards.

-

Their hair is carved as dense clusters of small raised bumps—about 80 across the scalp—to show short, coarse, woolly hair.

-

Each bump is rounded and evenly spaced, a painstaking method meant to replicate the tight coil of African hair.

Lachish (Assyrian Palace Relief – Siege of Judah)

-

The Judean captives are shown under guard, executed, or impaled.

-

Like the Nubians at Persepolis, they have short woolly hair, carved in rows of tiny raised knots across the head.

-

In some cases, the detail is so fine that nearly 100 small curls can be counted on a single figure.

-

Unlike the beardless Nubians, several Judeans also wear short curly beards, but the scalp hair is identical in texture and technique.

The Match

Both reliefs—separated by empire, geography, and context—use the same visual vocabulary: small raised bumps chiselled to represent short, tightly coiled hair. At Persepolis, they identify Nubians; at Lachish, they mark the people of Judah. Together they confirm a consistent artistic truth: the men of Judah were carved with the same hair texture as Africans.

Copyright 2024 Archaeology theme. All Rights Reserved.